Mobility mindset

Front-line workers are the people that are living and breathing their company’s products and processes every day. They are the ones who literally handle the nuts and bolts of the operation. They know what is working and what is sub-optimal from the product and process perspective. But inviting their creativity and effectively capturing their input is a big challenge for any manufacturing company – How do you help to unlock what they know? How do you operationalise their feedback? How do you share knowledge effectively between teams in different factories? As the sector considers its recovery from the incredibly challenging events of 2020, answering these three questions could deliver a step change in how your organisation works, by tapping into and prizing the knowledge of one of your key assets – your employees.

To unpick the answers to these questions, we were particularly interested in looking at the effect of mobilising employees to foster innovation in manufacturing. We conducted a large-scale study where we systematically analysed innovative ideas submitted by the workers and their economic impact in a multinational, multi-billion euro car parts manufacturer over the course of four years. Key to our analysis was matching mobile front-line employees to similar colleagues who did not travel to other plants. This allowed us to precisely estimate the mindsetmindsetcontributions originating from their mobility. Over the course of our research, more than 21,000 ideas were submitted by around 2,500 workers.

There were two key discoveries that stood out from our study:

- Significant productivity gains could be traced back to non-R&D employees: Shop floor and front-line employees frequently possess a wealth of hands-on production knowledge at a level of detail that far exceeds what is covered in manuals or is known to engineers.

- Staff mobility is central to unlocking innovation and organisational learning. Our study showed for the first time how strategically implementing front-line mobility (the short, focused, and purposeful exchange of staff members between different company sites) can substantially boost these employees’ contributions to innovation in manufacturing companies because it stimulates learning. As staff observe how different setups of similar manufacturing processes are linked to various performance outcomes, they acquire a more fundamental understanding of both how and importantly why these processes work.

We recorded that adopting the right approach; one that stimulates, objectively evaluates, and swiftly implements front-line ideas can unlock significant financial rewards. We found that employees’ ideas increased in value by 20,000 euros per month after a move, and this increase lasted for several years.

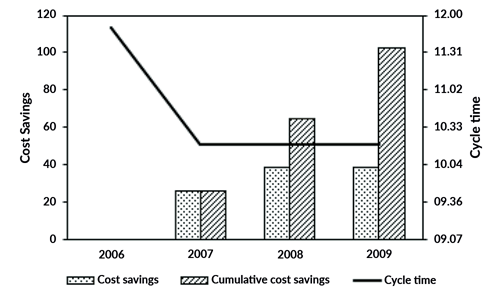

Cost Savings (over three years) Due to a Typical Process Optimization Idea Notes. Cost savings are given in thousands of euros. This improvement idea led to a 12.68% reduction in cycle  time (from 11:50 to 10:20). The idea was implemented in 2007 and led to cumulative cost savings of €102,770 (over three years).

time (from 11:50 to 10:20). The idea was implemented in 2007 and led to cumulative cost savings of €102,770 (over three years).

In fact, the average move created manufacturing improvements worth more than 100,000 euros within one month.

For a mobility strategy to be successful though, we identify three key principles that are important to consider at the outset:

1. The approach has to be purposeful, and problem driven. Employees should not be sent to other plants to passively observe operations or receive training, or as a reward. It is important that moves are tied to a specific and operationally relevant task. In our study, employees were regularly sent to other factories to support local problem-solving, such as when the production process was facing quality issues. These visits were kept to a maximum of two weeks and involved an intense immersion in the local factory’s operations. In doing so, employees became deeply embedded in the context of the plant and achieved maximum interaction with its staff, processes, and machinery. This very hands-on, focused approach to front-line mobility is instrumental to knowledge transfer and learning.

2. Identify similar processes, machinery and products when deciding the exchange: If processes, machinery, and products differ too much between two plants, the gap between their existing knowledge stocks becomes too large for any meaningful knowledge transfer and learning to take place. If two plants are too different, knowledge from one plant may simply not apply to the other. In our view, turning to related units in similar contexts is better than visiting technologically advanced but unrelated ones.

3. Limit how many employees participate and how often exchanges take place. At the car parts manufacturer we studied, about three per cent of the workforce visited another plant each year. Involving more employees much beyond that in exchanges may increase costs, such as those incurred from covering staff members’ absences at their home factories. In addition, while there was no limit to employee learning, we found that knowledge transfer started to decline after about ten exchanges per factory pair and year.

From this intriguing study we were able to draw a key conclusion: adopting a mobility mindset can be key to realising the creativity and innovations possible from front-line workers. Giving workers the opportunity to understand more about what they know, to share their knowledge and to learn from other people’s experiences through mobility is also motivating and empowering. We were impressed at the high calibre ideas that the mobile workers contributed, that would have otherwise gone undiscovered. Especially in the post-Covid world, it takes careful planning and strategy to roll out mobility across an organisation in a meaningful way, but in the long-term, productivity gains and financial benefits would be worth the hassle.

Philipp B. Cornelius, Bilal Gokpinar and Fabian J. Sting

Philipp B. Cornelius (cornelius@rsm.nl) is assistant professor of technology and operations management at Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University.

Bilal Gokpinar (b.gokpinar@ucl.ac.uk) is head and professor of operations, technology, and innovation at the UCL School of Management at University College London.

Fabian J. Sting (sting@wiso.uni-koeln.de) is the chair of Supply Chain Management — Strategy and Innovation at the University of Cologne, as well as chaired professor of digital supply chain innovation at Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University.

The UCL School of Management is the business school of University College London, one of the world’s leading universities, consistently ranked in the global top 20 for its academic excellence and research. The School offers innovative undergraduate, postgraduate, PhD and executive programmes in Management, Entrepreneurship, Business Analytics, Business Information Systems, and Finance, designed to prepare students for leadership roles in the next generation of innovation-intensive organisations.

www.mgmt.ucl.ac.uk